[Apologies to those of you who may have received a draft version of this post earlier this evening. We’re still getting used to the functions of this new blog! Thank you so much for your patience as we work out the kinks.]

Day eleven, technically, marks the end of the #MyMilitaryAncestor challenge set forth by Canadian genealogy blogger, Patricia Greber. Patricia’s call to arms encouraged family historians around the world to pay tribute to their veterans and war dead, honouring them for the great sacrifice they made to ensure our freedom. Of course, the conclusion of this challenge does not mean that our remembrance or gratitude expires as well — but we think it has been a lovely success, don’t you?

The “Big Finale” with which we choose to conclude the #MyMilitaryAncestor challenge is the overall horror found in the unrelenting struggle and loss that became monotonous, regular, every-day occurrence for our service men and women. The following, sadly, is representative of the average soldier’s story.

Honouring Our Military Ancestors Challenge – Day Eleven

On the march, despite his flat feet

Irish-born, but living in Canada since before 1901, Private Robert Anderson was a single man and in his mid-thirties when he joined the Canadian Expeditionary Forces in 1916. His medical records indicate that he suffered from the “disease” of flat feet.

Despite this medical “condition”, Robert was part of the 85th Canadian Infantry Battalion, which he joined on 11 November 1917, just after Passchendaele. Many battalion members had been killed at that historic battle and the battalion was resting at a camp near Caestre, France, while it was brought to normal strength by the arrival of new recruits.

For about a month, the men had time for sports, concerts and movies. But the battalion was soon on the march south and on 23 December 1917, Robert and his fellow infantrymen found themselves on the front line in Avion (France).

It was a bitterly cold winter day, reports Lt. Col. Joseph Hayes in his 1920 book, The Eighty-Fifth in France and Flanders, and “[t]here were no dugouts or shelters or other accommodations” in the trenches to protect the men against the awful weather. Adding to the misery, Christmas day dinner consisted of army rations eaten “to the accompaniment of Hun ‘Pine Apples,’ whiz bangs, five-point-nines and high explosives.” It was only on New Year’s Eve, when they returned to a camp on the grounds of the Chateau de la Haie (France), that the battalion was able to finally sit down to a Christmas dinner of turkey and all the fixings.

On 12 March 1918, the battalion broke camp and returned to the Vimy area. Lt. Col. Hayes reports:

“There was a good deal of tension all along the line now. It was known that the long talked of big German drive for final victory was now near at hand. The numbers in the line were being increased and every section was put on a siege basis. The storm broke on Thursday March 21st, against the Imperial 5th Army in the Amiens Sector.”

Sadly, Robert was “dangerously wounded” (medical report) on 20 March 1918, arriving at No. 1 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station with shrapnel wounds on his left side, leg, back, and arm. Robert died on 21 March 1918 and was buried the next day at Houchin British Cemetery (France).

This brief biography is an extract from one of 300 written by volunteers for the British Family History Society of Greater Ottawa (BIFHSGO), which maintains a database on the 879 soldiers who died at the No.1 Canadian Casualty Clearing Station. Canada’s casualty clearing stations, located within a few miles of the Front, were one of the most important links within the Canadian Army Medical Corps for the treatment of Allied wounded soldiers during WWI.

For more information about Canada’s No. 1 Casualty Clearing Station or to start searching this database, please click on THIS LINK.

A list of all ten of our previous posts in the #MyMilitaryAncestor Challenge series:

Day One – Infantryman “undoubtedly saved lives” at Passchendaele

Day Two – War was a family affair

Day Three – Measles, Mumps and the Military

Day Four – God who knows best has called you to rest

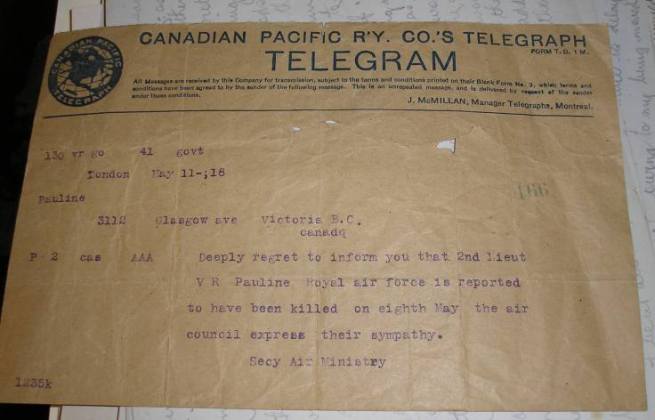

Day Five – “I expect you will have heard of the death of…”

Day Six – The horror of gas attacks

Day Seven – Corkscrewing away from a Junkers 88

Day Eight – Unexpected engine trouble ends pilot’s career

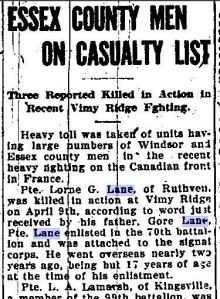

Day Nine – Over the Top, A Canadian Soldier Gives his Best at Vimy

Day Ten – Bomb thrower gassed, shelled, participates in Christmas exchange

Please share your thoughts with us in the Comment Box below! And don’t forget to share via social media to help our military ancestors go viral this November!